Navigating Tap Sampling Changes Under the LCRI and LCRR

Recent laws and legal challenges have created uncertainty: The Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) could be replaced with the previous Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR). Under either rule, water systems must prepare for stricter monitoring requirements, lead service line (LSL) sampling, and potential action level exceedances. Min Tang, PhD, explains how to avoid noncompliance sampling risks under the LCRR and LCRI.

Min, can you explain the biggest tap sampling changes between the LCRR and LCRI?

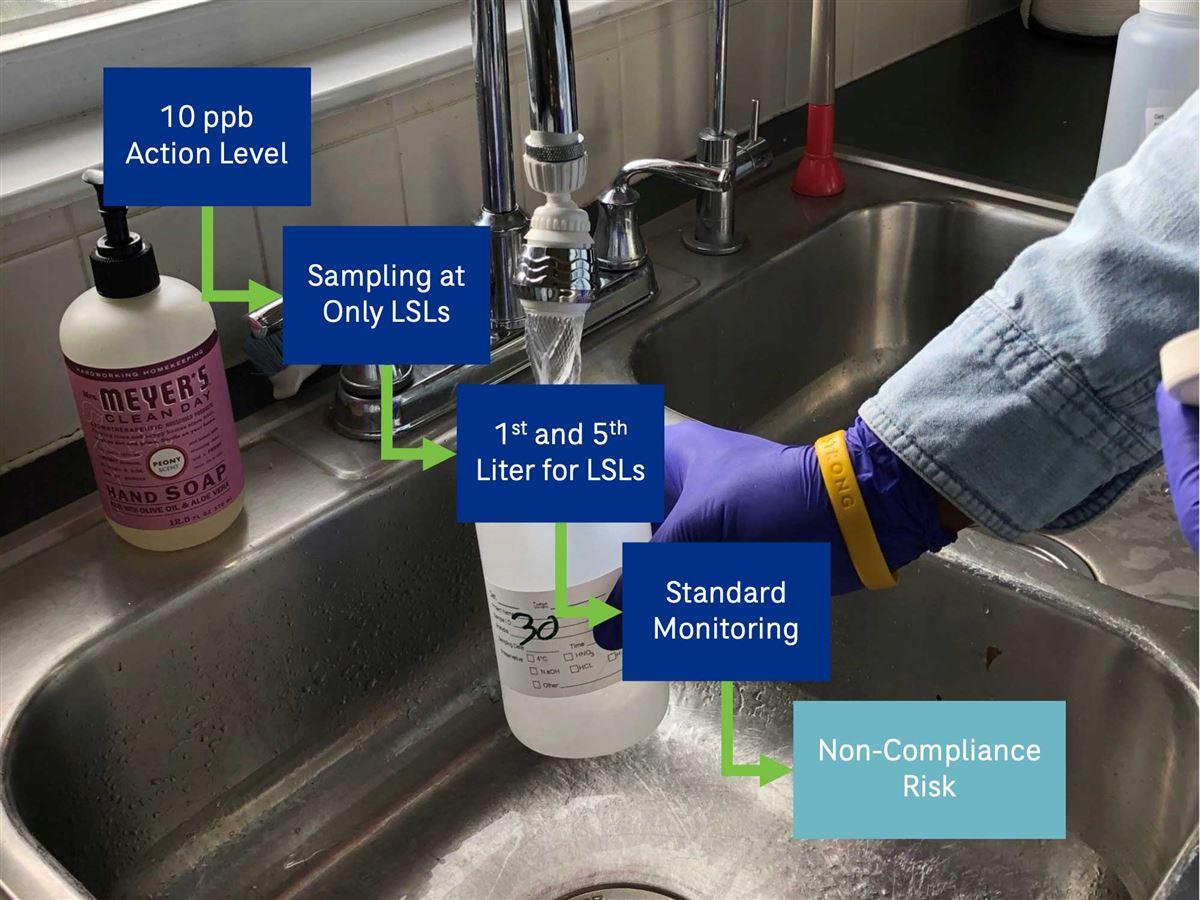

One of the most significant changes is the action level adjustment. Under the LCRI, the action level drops from 15 parts per billion (ppb) to 10 ppb, eliminating the LCRR’s 10 ppb trigger level. While water systems will continue to be assessed under the 15 ppb action level through 2027, starting in 2028, the new 10 ppb standard will take full effect. This lower action level will put more systems into corrective action territory.

Another major shift involves the sampling site pool. Under the current Lead and Copper Rule (LCR), systems with LSL sites could include up to 50% (or more) of their samples from sites with copper pipes containing lead solder. However, under both the LCRR and LCRI, the sampling site pool must consist entirely of LSL sites, if available. This means utilities must prioritize homes with known LSLs for water sampling before considering other sites.

Tap monitoring has also changed. Under the LCRR, the tap monitoring schedule and sites depend on the 90th percentile lead level relative to the trigger level (10 ppb) and action level (15 ppb). Under the LCRI, beginning in 2028, water systems with LSLs or galvanized requiring replacement (GRR) will be required to conduct standard monitoring—two consecutive six-month monitoring periods at the standard number of sites. Many systems with LSLs or GRRs will return to standard monitoring in 2028. In 2029, water systems will be eligible for reduced tap monitoring if their 90th percentile lead levels remain below the new 10 ppb action level for two consecutive six-month periods.

How do these changes affect the way sampling is conducted?

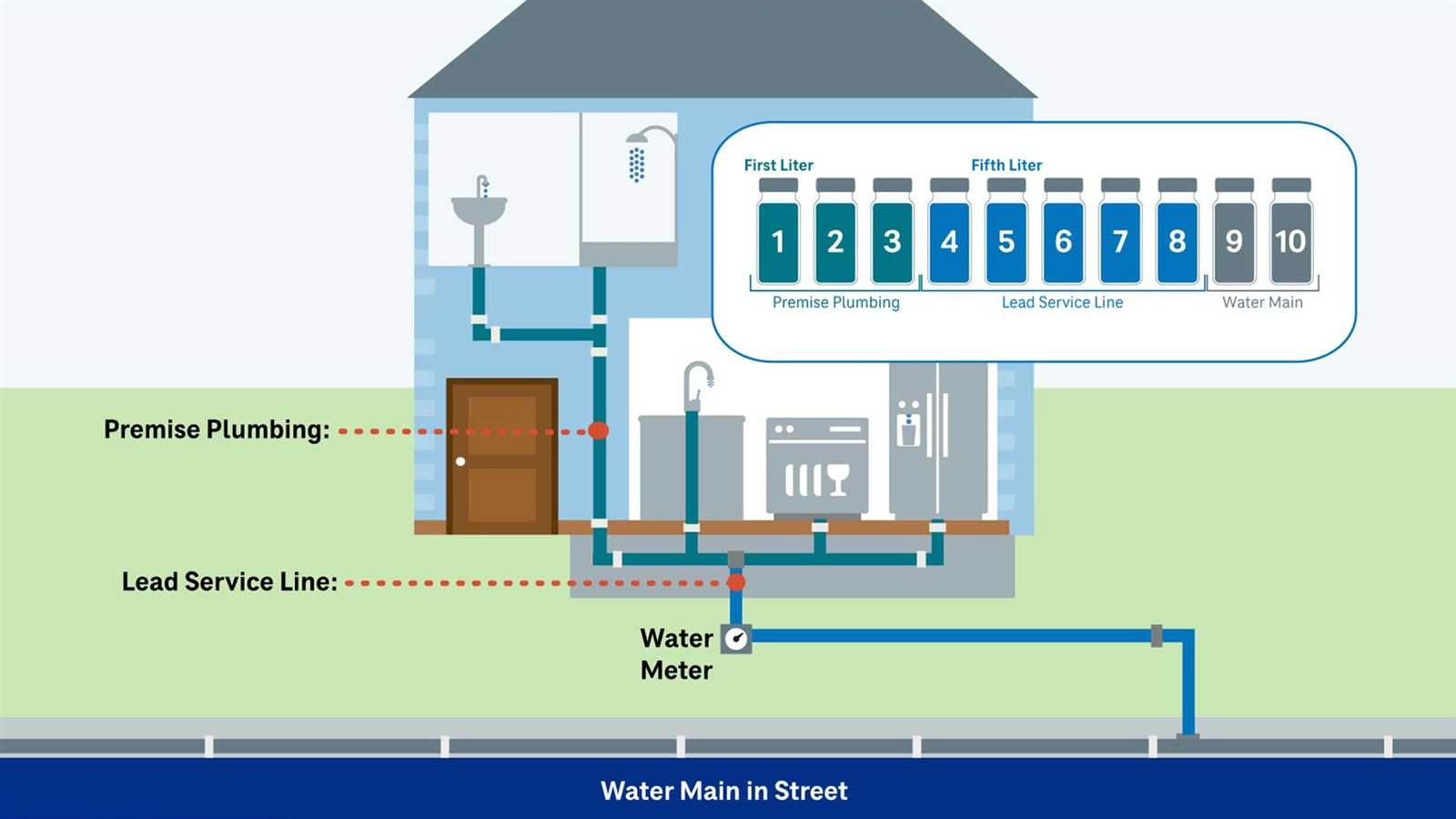

The sampling methodology is changing significantly. Under the LCRI, water systems must collect both first- and fifth-liter samples at LSL sites, using the higher of the two results for the 90th percentile calculation. Under the LCRR, systems were only required to collect fifth-liter samples at LSL sites.

This is significant because the fifth-liter sample is more likely to capture lead leached from the LSL, whereas the first-liter sample primarily reflects internal plumbing sources, such as brass fixtures or lead solder. Our research, which analyzed 137 LSL profiles across five Midwest and Northeast water systems, found that in 56% of cases, the fifth-liter sample had two to four times higher lead levels than the first-liter sample. In 18% of cases, it was more than five times higher.

For many systems that historically remained under the 15 ppb action level, this change could push their 90th percentile above the new 10 ppb action level for the first time—potentially triggering new compliance requirements.

What do water systems need to do to prepare for these changes?

The first priority is updating sampling plans before 2028. Utilities need to ensure their sampling pools prioritize the highest-risk homes with LSLs, which ties back to maintaining an accurate LSL inventory. Systems also need to begin testing premise plumbing materials, as regulators will expect documentation on lead solder, brass fixtures, and whether homes use point-of-use filters.

Another key step is evaluating the water system’s risk of exceeding the 10 ppb action level and planning for corrosion control treatment (CCT) studies. Many systems that previously stayed under the 15 ppb action level may now exceed the new 10 ppb threshold due to changes in sampling protocol, calculation methods, and tap monitoring requirements. More systems will be required to conduct pipe-rig studies as part of a CCT study. Depending on state-specific requirements, it may take up to five years from completing the pipe-rig study to implementing full-scale chemical treatment, so starting early is crucial if a future action level exceedance is possible.

Are there any differences between the LCRR and LCRI when it comes to compliance actions?

Yes. One of the biggest shifts is that the LCRI requires mandatory full replacement of LSLs and GRR service lines, regardless of the 90th percentile lead level. Under the LCRR, mandatory replacements were only triggered when the 90th percentile exceeded the trigger level (10 ppb) or action level (15 ppb).

The LCRI also introduces a firm requirement for water systems to develop and complete lead service line replacement (LSLR) plans. Under the LCRR, systems only needed to submit a replacement plan; under the LCRI, they must actively implement it.

Additionally, under the LCRI, systems with three or more lead action level exceedances in a five-year rolling period must provide filters and conduct additional public outreach. The LCRR has no additional filter or outreach requirements for multiple exceedances.

Public education and notification timelines are also stricter. While the LCRR required utilities to notify the public within 24 hours of an action level exceedance, the LCRI expands these requirements, mandating more proactive education campaigns and additional outreach to impacted households.

The best course of action is to focus on reducing unknowns and preparing for compliance challenges now.

What steps should water systems take now to minimize noncompliance risks?

Start proactive sampling at LSL sites now. Even though the LCRI won’t take effect until 2028, utilities should begin collecting both first- and fifth-liter samples at LSL sites to assess risk levels. If early results show elevated lead levels, systems can adjust corrosion control strategies and LSLR plans ahead of time.

Another critical step is updating service line inventories. If a system can confirm it has no lead or GRR lines, it can remain on reduced monitoring, avoiding some of the stricter LCRI requirements.

Finally, utilities should regularly meet with state regulators to ensure their sampling protocols align with state-specific rule interpretations. Some states that have already adopted the LCRR require comprehensive premise plumbing inventories, meaning water systems in those states need to take extra steps to document internal plumbing materials.

Any final advice for utilities preparing for these changes?

Expect stronger enforcement and increased oversight. The LCRI allows water systems to defer corrosion control treatment if they commit to removing all LSLs and GRRs within five years—but that’s a challenging timeline for many utilities.

If the LCRI is repealed and the LCRR is reinstated, some procedural changes may occur. However, the fifth-liter sampling requirement will remain, meaning that in systems with LSLs, lead levels will likely be higher than what systems saw under previous monitoring methods.

Regardless of potential regulatory shifts, the best course of action is to focus on reducing unknowns in service line inventories and preparing for these compliance challenges now.

Min Tang, PhD, EIT is an environmental engineer with over 10 years of experience in distribution system water quality, corrosion and corrosion control assessment, microbial water quality management, and water treatment.