PFAS Fingerprinting and the Case for Source Control

Wastewater experts, like CDM Smith environmental engineer Eric Spargimino, warn that treating for PFAS at the point of discovery (i.e., drinking water sources, wastewater, landfills, etc.) is not an adequate solution and will place an impossible burden on utilities downstream of where the contamination originated.

“If these utilities and other receivers of PFAS aren’t provided treatment options and funding for PFAS mitigation and the tools needed to identify and control upstream sources of PFAS, new regulations will continue to disrupt operations and management,” said Spargimino upon the release of an industry report on PFAS and biosolids that suggested costs are in the billions of dollars.

In a letter to Congress outlining concerns with pending PFAS regulations, 13 industry representatives, including several that contributed to the biosolids report with Spargimino, urged lawmakers to protect utilities from significant cost burdens and argued that “municipal drinking water and wastewater utility ratepayers could face staggering financial liability to clean up PFAS.”

Controlling upstream sources, the initial producers or users of toxic PFAS compounds like PFOA and PFOS, has become a bigger priority than ever before. In EPA's PFAS Strategic Roadmap, the agency lays out several plans for source control, like leveraging permitting to reduce discharges and requiring pretreatment in certain cases.

But before we can stop the flow of PFAS, we have to connect the dots.

Fingerprinting can give us clues to where utilities should focus their PFAS source control efforts.

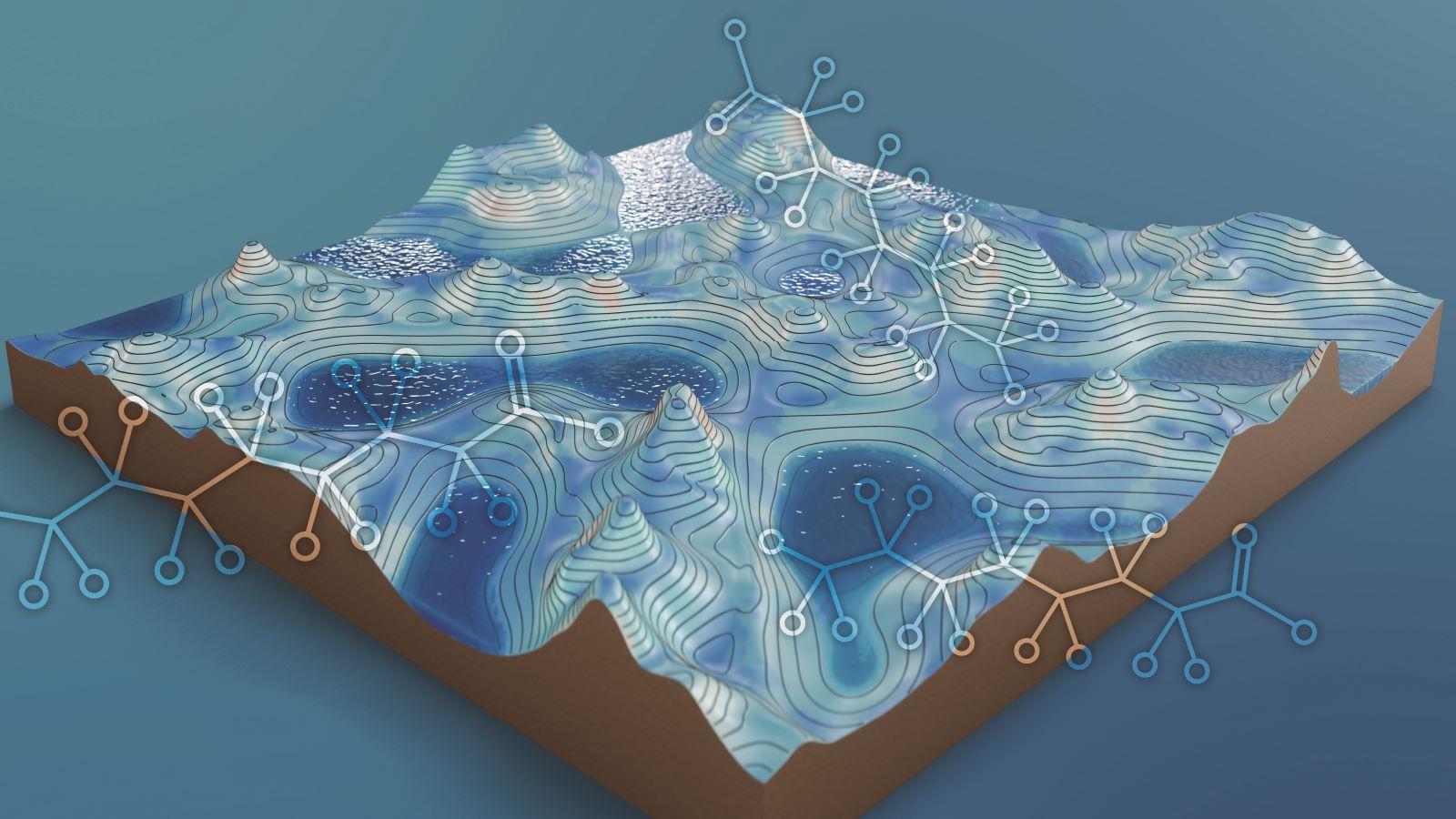

One of the most dangerous traits about PFAS, their persistence, along with their diversity also presents an opportunity to conduct forensic analysis to try and identify sources of PFAS observed in utilities or the environment. During the past several years, state and federal sampling directives have led to a boom in collecting PFAS data at water and wastewater utilities and within the environment and creating large databases that can be publicly accessed. Under the right lens, environmental scientists are counting on this new data to show not just where PFAS exist but also the points at which they originate.

Fingerprinting

Forensic analysis relies on using the variability in PFAS composition (12,000 PFAS and counting) of different products (e.g., AFFF-foams used for firefighting), with different PFAS products often having unique chemical signatures. Utilities such as sewers receive discharges from a variety of sources—residential, industrial, commercial—containing multiple types and concentrations of PFAS products. Therefore, tracing sources of specific PFAS known to be toxic, like PFOA and PFOS, is difficult and many forensic tools are being developed to interpret the new sampling data flooding to online PFAS trackers.

“Just one sample for PFAS can show a large number of detections of individual analytes, depending on the analytical method used," says Chris Gurr, PFAS remedial investigation discipline leader at CDM Smith. "We know that different sources of PFAS have different compositions of PFAS."

California’s GeoTracker receives thousands of private and public sector analytical and field data from sites that impact, or have the potential to impact, water quality in California.. With the help of a statewide sampling directive, California Water Boards now operates a special GeoTracker for PFAS. The Minnesota Department of Health has published an Interactive Dashboard for PFAS Testing in Drinking Water and Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection has the Maine PFAS Mapper.

Tools like these are indispensable for PFAS forensic investigators, providing environmental engineers and scientists the data to find relationships and indicators of specific PFAS sources. And that is a big step forward toward identifying, and ultimately, controlling sources of PFAS releasing these chemicals into our utilities and environment. "We’re working now to tease out these compositions as unique fingerprints for a source – and then track those fingerprints downstream, either into the sewer network or in surface water or groundwater resources," says Gurr. "Fingerprinting can give us clues to where utilities should focus their PFAS source control efforts.”

PFAS datasets are large, and as a result we can leverage computer programming and statistics a lot more than we’ve ever been able to do before.