Green Infrastructure Guidelines for Corridor Projects: What You Need to Know

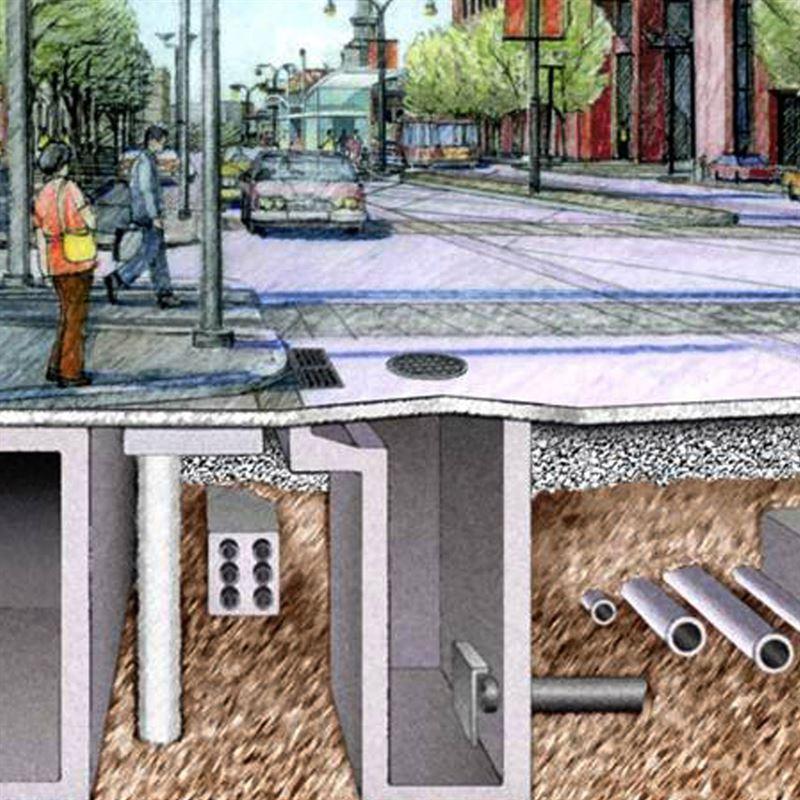

Green infrastructure is most commonly used to help improve water quality and reduce combined sewer overflows in densely populated cities, but the concept is increasingly being used by the transportation industry to help manage stormwater where it falls and improve water quality. Some dense, urban communities are taking an area-wide approach, installing small-scale green infrastructure practices throughout the watershed, such as right-of-way bioswales and porous pavement. Others with more available space are separating combined sewer systems and conveying separated stormwater to retention/detention basins downstream. Whatever the approach, the benefits of effective stormwater management, improved aesthetics, cooler temperatures and added resiliency can make the decision to implement green infrastructure an easy one.

But green infrastructure is about much more than planting trees and building rain gardens. And the two most common questions that arise— ‘who will maintain it?’ and ‘how will we pay for it?’—must be addressed in the planning phase.

Ginny Roach, PE, PMP, BCEE, CDM Smith’s national leader in green infrastructure planning, design and construction, has helped municipal and private clients across the U.S. with their stormwater management plans. Thanks to decades of experience conducting site visits, interviewing staff, preparing design drawings, and constructing green infrastructure, Ginny and her team have developed a list of guidelines to assist cities in designing, operating and maintaining successful green infrastructure programs.

Guideline #1: Develop design standards

Having a group of standard design details and specifications will help to save considerable planning and design costs, and make construction easier over time as contractors become familiar with and understand the designs. In addition, these design standards and procedures help make leaders and stakeholders feel confident that green infrastructure practices are being planned and constructed properly.

Guideline #2: Utilize asset management tools to track success

As one of the first steps in building a best-in-class green infrastructure program, cities should identify a system for quantifying, tracking and monitoring program benefits. A number of illustrative, interactive tools have been developed; many include mapping components to help monitor program benefits such as water quality improvements or tree canopy coverage changes. Others include regulatory calculators so cities can estimate compliance on projects with multiple types of green infrastructure installations.

New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYCDEP) and CDM Smith, for example, developed a dashboard and asset management system called GreenHUB to track the progress of green infrastructure construction, as well as to provide a digital ‘file cabinet’ for storing design drawings, reports and other submittals over the life of each asset. The system includes an interactive map to help keep the community engaged and show them what is happening in their neighborhoods.

We recognize that one size certainly does not fit all with regard to green infrastructure implementation. That’s why our approach is tailored to the specific needs of each urban community.

Guideline #3: Access available funding

There is a wide variety of funding methods that can be used for green infrastructure programs. Here is a look at how some major cities are funding their assets:

- Water and sewer rates: San Francisco*, New York City and Toronto (*San Francisco divided sewer charge into a sewer charge and a stormwater charge, but total charge did not change)

- Parcel tax: Los Angeles

- Stormwater utilities: Detroit, Philadelphia, Columbus, Cleveland and Harrisburg

- Grants and incentives: Milwaukee, New York City, Philadelphia and Houston

Guideline #4: Design with maintenance in mind

Lessons learned in the green infrastructure design process, says Roach, are "that not everyone wants a right-of-way bioswale in front of their house, porous pavement can be beautiful too, and hardscapes are easier to maintain because they are less susceptible to trash accumulation than rain gardens and bioswales." If vegetated systems are preferred over hardscapes, grasses provide better stormwater infiltration than plants based on a University of New Hampshire Stormwater Center study. Grasses are also easier to maintain than plants; they can be mowed, and there is a variety of ornamental grasses that are aesthetically pleasing.

Green infrastructure programs across the country are also addressing maintenance in a variety of ways. Cities like San Francisco have created youth programs that offer opportunities for students at local high schools and elementary schools to rehabilitate green infrastructure sites and help with general maintenance. Philadelphia created Soak It Up Adoption Mini-Grants, given to organizations to help maintain neighborhood green infrastructure. To give them time to get a maintenance division up and running, New Orleans has been including three years of maintenance in green infrastructure construction contracts.

Guideline #5: Foster community engagement

Community input and active involvement from local residents, businesses, district leaders and artisans promote acceptance, integration and ownership, explains Roach.

Nicholas Watkins, landscape architect at CDM Smith, highlights the importance of community engagement: "Done right, green infrastructure sites should not serve only as stand-alone free spaces, fenced off, and utilitarian in nature. They should be designed as restorative interventions into blighted communities, prioritizing aesthetics, community-specific amenities, and passive recreation space. Rather than taking the space to fix issues downstream, they give space back.”

Take, for example, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District (NEORSD), that included the work of local Cleveland artists in its Union Buckeye project. Poetry was inscribed in plaza seating areas surrounded by rain gardens (and located above subsurface storage systems), with custom-fabricated trench drains, a water tower sculpture and a bike rack symbolizing the water treatment practices within and under the plaza. This community engagement helped to beautify a previously downtrodden area while also spreading the word about the importance of water quality.

Guideline #6: Branding = buy-in

Program branding helps garner both internal and community-wide support. Cities have used program-specific logos, promotional videos, native-language speaking brochures, interactive maps, and other program materials to familiarize the public and keep stakeholders abreast of the program’s progress and success.

As Roach reminds clients, "we recognize that one size certainly does not fit all with regard to implementation. That’s why our approach is tailored to the specific needs of each urban community, as well as the regulatory requirements, zoning, rainfall patterns, soil types, groundwater elevations, topography and public interests of each project area."