AWWA Roundtable 2024: Navigating LCRI and PFAS Regulations

In the last year, EPA issued final Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) on October 8. Most of the LCRI requirements will go into effect in 2027. The agency also published much anticipated maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for six PFAS.

The American Water Works Association (AWWA) gathered a panel of utility managers, lawyers, scientists, engineers, regulators, and risk communication experts at the Chicago Hilton on December 5 – 6 for a well-timed roundtable called “Rules to Solutions: LCRI, PFAS, and Community Impact.”

From compliance to funding, the panel shared critical lessons learned and forecasts for the road ahead.

We have an open opportunity to build water-utility identity, with positive messaging.

PFAS compliance begins now.

The PFAS MCL announcement came with a rollout timeline, allowing five years for water systems to comply with the new thresholds. A lot could happen in that window, including changes to current guidance and even regulatory limits, spreading uncertainty across all sectors—water and beyond—that may be required to treat for PFAS.

The general consensus from experts is to proceed on the assumption that these regulations may change, but they are not going away.

Don't be a "silent provider."

One panel focusing on lead service line replacement featured the heads of the Newark, Chicago and Milwaukee water departments. Kareem Adeem is the Director of Newark Water & Sewer, where a successful lead service line replacement program has been in the public eye for decades.

“Communicating public health risk was the toughest part,” Adeem said.

Panelists shared their experiences talking with stakeholders, addressing the difficulty of communicating the importance of the LCRI, while at the same time avoiding alarmist language and generating fear. Having a portable story that can be told quickly helps prevent miscommunication, an ever-present pitfall for utility contractors, especially when dealing with sensitive topics like lead and PFAS.

According to Ruben Rodriguez, Senior Director of External Communications for American Water, PFAS hasn’t really taken hold of the public’s interest yet. Looking beyond PFAS, Rodriguez sees a similar level of disinterest when it comes to water contamination.

“We have an open opportunity to build water-utility identity, with positive messaging,” Rodriguez said during a panel on building trust and managing risk.

Kelley Dearing Smith, Vice President, Communications and Marketing at Louisville Water Company, urged attendees not be “silent providers.” By that, she meant a lot of water providers have little or no identity, despite water utilities being among the most reliable public utilities.

Many panelists reported an increased frequency with which they need to communicate with customers about water contamination in general. Water suppliers and their contractors can earn that trust when entering a community by partnering with active community groups like local environmental and public health advocates, as well as local trade associations.

"Get the Lead Out" panel, from left: Randy Conner, Commissioner – Chicago Department of Water Management; Jamie Rott, Superintendent – City of Rockford Water Division; Kareem Adeem, Director of Newark Water & Sewer; Pat Pauly, Superintendent – Milwaukee Water Works; Sandra L. Kutzing, Lead and Copper Strategy Leader – CDM Smith

How do we comply with the LCRI and PFAS MCLs without dramatic rate increases?

A significant challenge ahead of water utility managers is finding ways to meet the regulations without impacting ratepayers too dramatically. Utilities often need to increase staff and resources just to meet over-sized threats like lead and PFAS. That “ramp-up” has a cost, too, said Randy Conner, Commissioner for the Chicago Department of Water Management.

As commissioner, Conner heads Chicago’s lead service line replacement program. With about 350,000 service accounts, Chicago needed more plumbers trained in lead line replacement. There were just not enough contractors to do the work. To keep the project moving forward, the city arranged partnerships with local community groups that would help train new contractors from the service area.

Chicago’s “ramp up” shines a light on the most significant challenge facing water departments: funding.

Thomas Liu, managing director of Bank of America Securities, outlined the 6 principal methods water utilities have for funding:

- Grants

- Low-cost state funding

- WIFIA loan

- Bank financing

- Municipal bond market

- Private Money

According to Liu, the banking industry has shown a growing interest in financing projects for the water industry.

Additionally, federal dollars from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) give water utilities a chance to start replacing lead pipes ahead of the regulatory deadline. Since future funding isn’t guaranteed, utilities are encouraged to act early and take advantage of the support that’s available now. Starting sooner also opens up more funding options, which can help keep costs lower for residents.

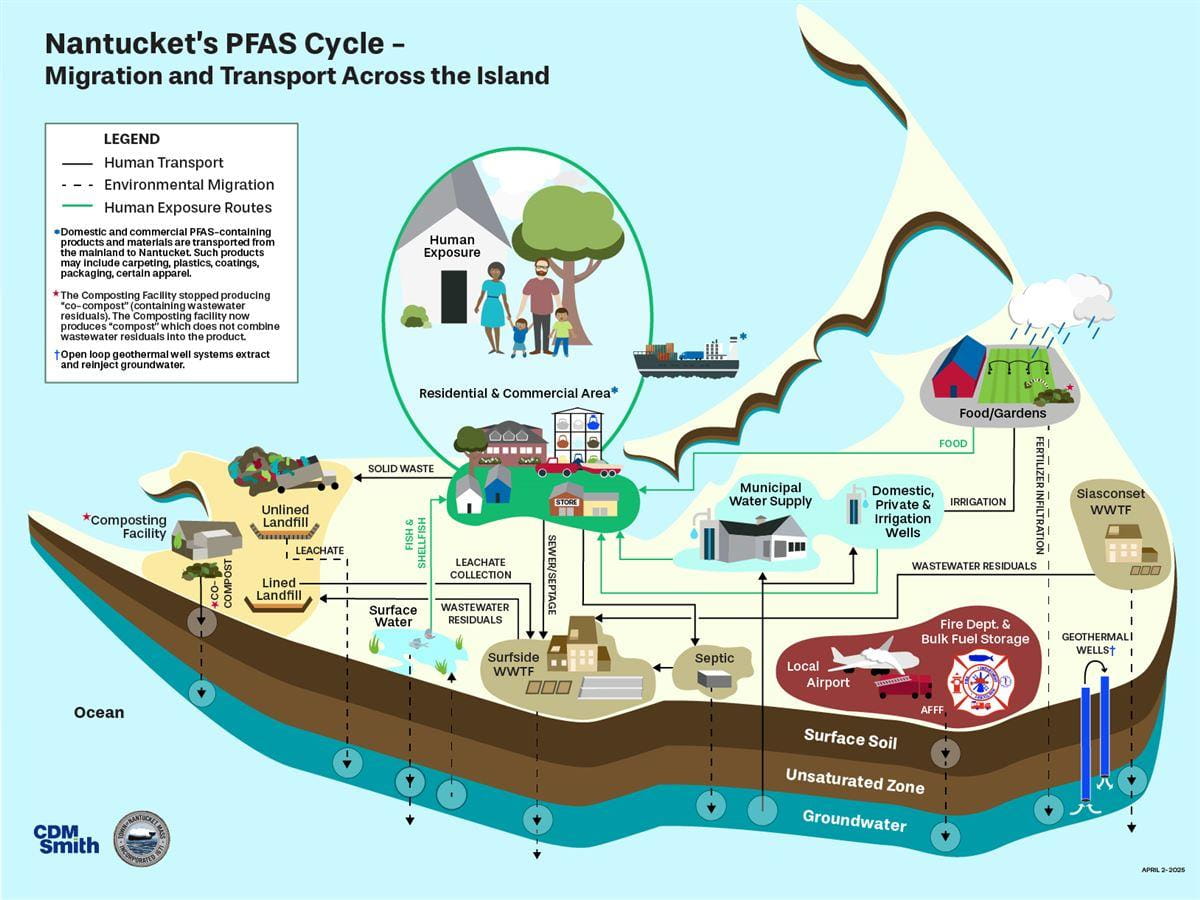

Break the cycle.

As some nationwide cost estimates related to PFAS over the next 10 years soar past $1 trillion, the water-supply industry has another potential cost to consider, one that could upend many budget forecasts. As PFAS receivers, utilities are seeking an exemption that would protect them from bearing the cost burden for upstream pollution. In simple terms, they don’t want to pay twice to treat the same chemicals.

While source control efforts increase and fingerprinting methods improve, water and wastewater treatment plants are currently vulnerable to getting pulled into the chain of responsibility.

PFAS could also have a significant impact on disposal practices. Without widely available and efficient means of destruction, water utilities could be stuck with storage of hazardous materials.

What's next?

To stay up to date with the latest in PFAS regulation, Lead and Copper Rule compliance, and water innovation, sign up for email updates from our experts.

I embrace change, and I'm always looking for opportunities to improve the way we do things.