AFFF Cleanout: Reduce Your Risk

The US Department of Defense (DOD) and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) are transitioning away from aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF) that have high concentrations of PFAS in favor of fluorine-free firefighting (F3) foams. Despite the increasing availability of the new F3 foams on DOD’s Qualified Product List (QPL), the transition may not be as easy as it sounds.

“Transitioning to F3 foam is far more complicated that just cleaning fire trucks,” says Jill Greene, AFFF Decontamination Lead at CDM Smith.

The federal maximum contaminant levels for PFAS call for extremely low environmental and drinking water levels, measured in the parts-per-trillion. That means an increased likelihood of aggressive remediation of PFAS in response to discharges of AFFF to the environment, down to an almost non-detectable level.

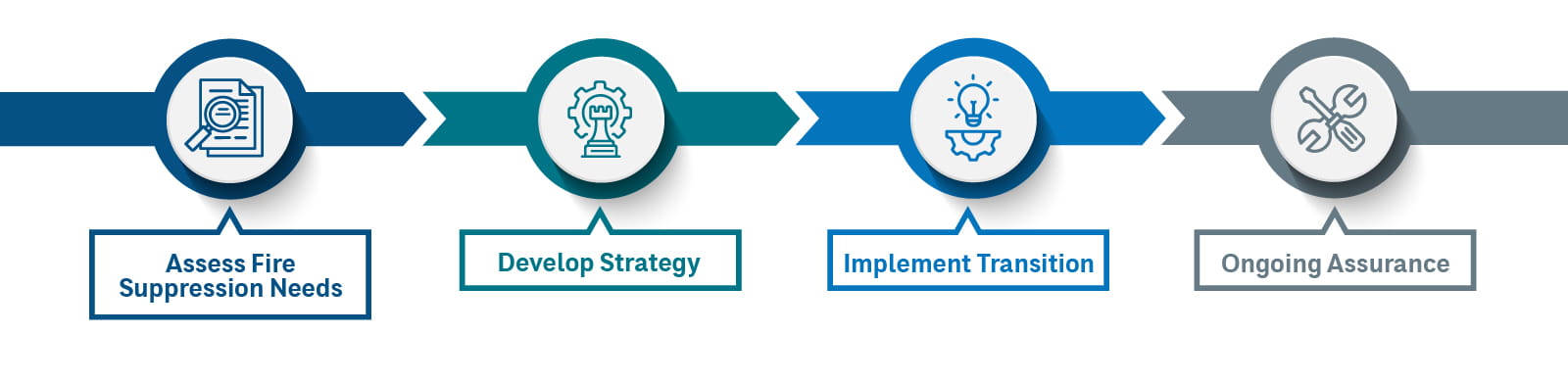

Developing a plan for transitioning away from AFFF is critically important to minimizing your risks and liabilities. Below are some key steps for a successful transition to reduce impacts to human health and the environment from PFAS:

Assess your system.

Assess your system.

If sufficient decontamination is not performed, residual PFAS stuck to surfaces as supramolecular assemblies will contaminate the F3 foam. PFAS structures disassociate over time, becoming a secondary source of PFAS in F3 or rinse solutions. This is known as the “rebound effect,” which may not appear until long periods of time following the rinse. This poses a major challenge since fire suppression systems can only be out of operation briefly.

Strategize for maximum efficiency.

When implementing AFFF cleanout procedures, water is not an effective solvent and should not be relied upon solely. A variety of solvents and additives have been tested for their ability to clean PFAS-impacted surfaces. However, due to differences in fire truck models, operation patterns, and adherence to protocols, direct comparisons are difficult.

We recommend that an aggressive quantitative surface swabbing method be used to quantitatively assess the mass of PFAS on surfaces to:

- Appropriately characterize PFAS on surfaces

- Demonstrate effective decontamination

- Assess the future potential rebound into F3 foams

Transitioning to F3 foam is far more complicated than just cleaning fire trucks.

Implement cleanout promptly.

An efficient onsite cleaning and rinsing protocol for the interior surfaces of PFAS-impacted firefighting infrastructure should be carried out promptly to avoid extended system downtime. Individual components from fire suppressant systems will need to be decontaminated or replaced to reduce the potential for residual PFAS to leach into new F3 products.

Our research has identified that the most effective method to remove these assemblies and deliver effective decontamination is via a combination of:

1. A non-volatile solvent (Increased temperature)

2. Surface Attrition

Following decontamination, sampling to determine the effectiveness of cleaning should be performed on the surfaces of the equipment components themselves, such as foam tanks and piping, to demonstrate how much PFAS remains. Unfortunately, the use of target analyses like EPA Draft Method 1633 will fail to detect the vast majority of PFAS that have been used as fluorosurfactants in firefighting foams. Instead, the total mass of PFASs needs to be estimated using analytical technologies such as the TOP assay and combustion ion chromatography methods.

Stay Connected for Ongoing Support

Stay Connected for Ongoing Support

The science in this field is continually advancing. In 2022, CDM Smith’s Dr. Ian Ross, in collaboration with two global laboratories (ALS and Eurofins), developed and proved the efficacy of a swab method to assess the mass PFAS on the surface of impacted pipes. Sampling of water rinses is an ineffective method for demonstrating successful decontamination as these data provide no indication of the PFAS mass left behind that will result in rebound.

For the latest news coming out of our Research and Testing Laboratory in Bellevue, WA, sign up for our Breaking Down PFAS newsletter.